The central argument of Cut Through! is that our information environment has changed more quickly than our communications practice.

To catch up, we need to understand what has changed and why.

In this series, I argue that our information environment has become more “D-FACC”:

Democratised. Almost anyone can read, access or publish anything.

Fragmented. With more personalised and siloed information streams.

Abundant. Content has become infinite as the cost of creation and distribution has plummeted.

Corroded. Misinformation travels as easily as truth as algorithms value what captures attention above all else.

Concentrated. Power in the market rests with the decisions of a few tech companies.

Part 1, looked at how these changes began in the 1990s when Google Search swept away traditional information gatekeepers.

In this chapter, we are a decade on in the 2000s, and looking at two launches that accelerated these trends.

Part 2: The start of the scroll.

Anyone who has seen Aaron Sorkin’s film ‘The Social Network’ will know something of the creation of Facebook.

Set up by Mark Zuckerberg and his college roommates in 2004 as a private network for Harvard students, it launched to the public in 2006.

By 2012 it had one billion users.

The invention that really matters for our purposes isn’t actually the website itself, but what sat at its heart: the News Feed.

Originally, Facebook consisted of a series of user profiles. It was like each person having their own webpage. You had to visit a friend’s page to see what they had posted.

The News Feed changed that by creating a constantly updating stream of everything your contacts were posting.

For the first time, people didn’t seek out information. Information came to them.

That small design change made Facebook more than a social networking tool. It became a publishing platform, and its users became publishers.

It signalled the beginning of infinite and abundant volume. Previously, when you visited a friend’s page, you came to the end of their updates. But the News Feed was endless.

I am going to return to Facebook next week, because the innovation I think is most important came later. It was hardly noticed by users at the time, but it might be more responsible for the media environment we inhabit today than any other change.

That’s for next week. Before then, we need to stay in the 2000s and take a look at the hardware that made our abundant information environment and attention economy possible.

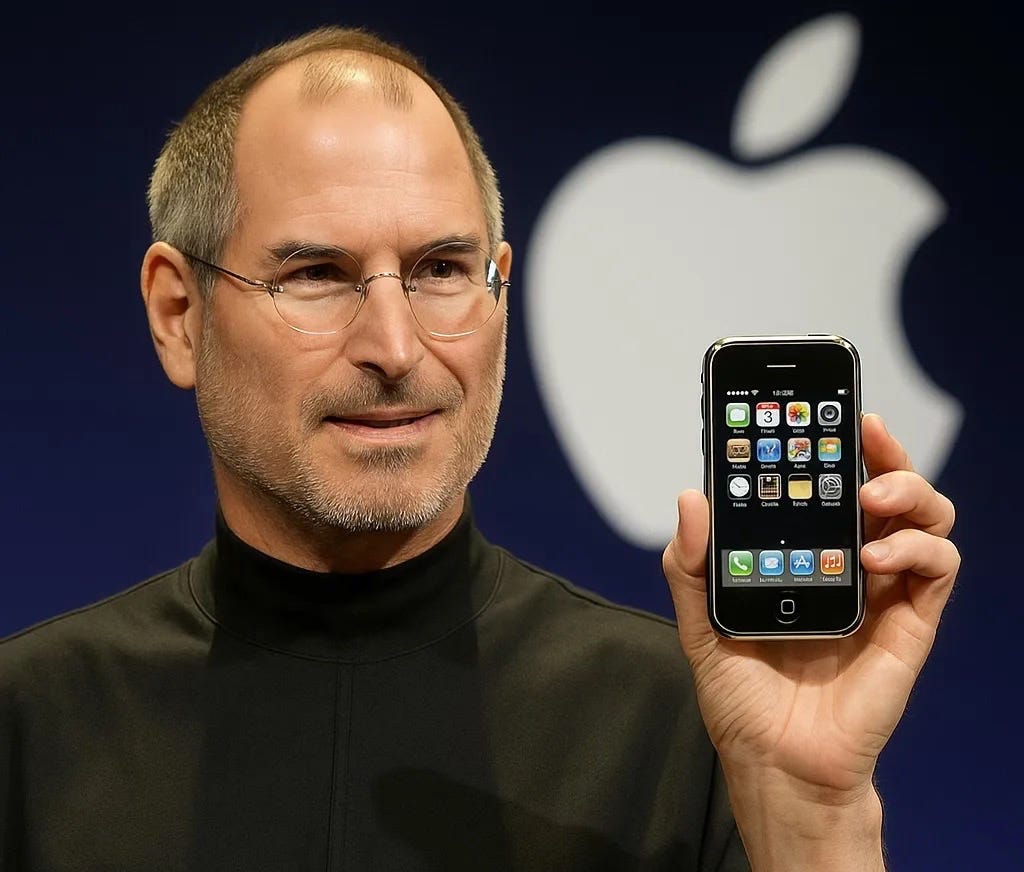

The launch of the iPhone

Unlike the other figures in this series, Steve Jobs was not a student running a start-up. By 2007, he was already a legend.

In 1984, he had co-founded Apple and introduced the Macintosh, which revolutionised the modern personal computer.

In 2001, he had introduced the iPod, which upended the entire music industry.

Given that sequels rarely surpass the original, it’s remarkable that Apple’s most significant contribution came with its third act.

Watching a video of Steve Jobs unveiling the iPhone in 2007, the language feels odd today.

He announces that he is introducing three new products:

“a wide-screen iPod with touch controls”

“a revolutionary mobile phone” and

“a breakthrough internet communicator”

And then comes the twist - they are all the same device!

The crowd goes wild, especially for Apple’s first phone, and yet the truly revolutionary nature of the announcement wasn’t really apparent at the time.

The real revolution wasn’t the phone. It was the screen.

The world goes touchscreen

Before the iPhone, popular smartphones like the Blackberry were 40% buttons and 60% screen. There were touchscreen devices around, like the PalmPilot, but they required a stylus and as Steve Jobs said at the launch:

“Who wants a stylus? You have to get them and put them away, and you lose them. Yuck! Nobody wants a stylus … We’re going to use the best pointing device in the world. We’re going to use a pointing device that we’re all born with … We’re going to use our fingers”.

Apple created a phone that was almost all touchscreen.

This new hardware and operating system, combined with the software of new social media platforms like Facebook, and the connectivity of 3G networks, transformed how people consumed information.

Hardly anyone scrolled before 2006. But with the internet now in our pockets, the scroll had begun.

News, entertainment, work updates, gossip, outrage, memes, marketing - all of it was collapsed into a single infinite feed with more always waiting below.

The end of the homepage

The iPhone mobilised and personalised the web. Each of us started to carry a customised, constantly updating stream of content tailored to our habits and interests.

Crucially, and I think unexpectedly, it also changed what content succeeded.

Attention was no longer earned through authority, it was won second-by-second through emotion, relevance or delivering a visual punch.

In other words, by stopping the scroll.

As information became abundant, communication moved from being a contest of ideas to a contest for interruption.

A never-ending attention loop

The iPhone created a new kind of relationship between people and information. By combining social-media feeds with push notifications and apps, it formed a never-ending attention loop.

Every buzz or red badge was a behavioural science prompt that there might be something new or important, and our brains are wired to respond. (Even as I write this, I feel compelled to respond to a buzz from my phone)

Contrary to popular belief, the brain chemical dopamine is not really about pleasure; it’s about anticipation. It’s a neurotransmitter that surges when you anticipate a reward, driving you to seek it out. It is the wanting that is dopamine’s primary role, not the enjoyment of the reward itself.

Every scroll of a smartphone promises a potential reward. Every anticipation of a possible social media ‘like’ is a small hit of personal validation.

Because this has happened to all of us, it is easy to underestimate the scale of the change we are talking about.

Think about it like this. Before the iPhone our phones were a tool for us to use (and they looked like one). After the iPhone they were a behavioural environment we inhabited - a black mirror that rewarded constant checking.

For communicators, this changed our competitive environment. We were now competing for habit. To be noticed, a message had to fit naturally into the small frequent moments of everyday scrolling.

The new grammar of communication

Communicators had to rethink their approach to length and timing for this new environment. Long-form press releases gave way to arresting visuals. Carefully drafted statements were ignored.

The smartphone reoriented the screen too. Vertical frames became dominant. Portrait imagery, designed for the iPhone, began to compete with landscape imagery designed for TV and cinema. Typography had to be legible at a glance while you were sitting on the bus. Logos had to work as app icons.

Tone changed too. The distance between organisation and audience collapsed, and the public and private became blurred. People were now experiencing your communication through a device that also delivered photos of their children and cat videos.

Anything that felt too institutional jarred against the intimacy of the medium. The best communicators learned how to sound like relatable people rather than distant press offices.

The consequences for communicators

The iPhone didn’t just change our devices, it changed our behaviour. Three lessons stand out for communicators:

1. Design for the thumb, not the desktop

Most communication is now consumed on a phone, often one-handed and on the move. If you weren’t optimised for mobile then the danger was that you weren’t seen at all. Design and language need to be built for where people read, not where you write.

2. Think moments and messages

Smartphones have fragmented attention into short, habitual checks. Communicators who succeed design content that fits these natural rhythms: brief, useful or emotionally resonant. However, this doesn’t mean abandoning long-term strategy. The danger is that digital teams produce content confetti. Every micro-moment where you cut through must still ladder up to a coherent, consistent narrative. Without strategic clarity, you risk creating noise that wins seconds of attention but makes no difference to outcomes.

3. Build intimacy at scale

The phone is one of the most personal objects people own. Messages that feel human or useful cut through, those that feel remote, self-interested or corporate do not. The challenge for communicators is to combine reach with authenticity. To sound like a person, not a brand, while still serving a strategic purpose for your organisation.

The device that changed behaviour

The iPhone proved to be far more than Apple’s first phone. Together with social media it helped create an environment where people live through their news feed.

If you want a D-FACC shorthand for what just happened: the News Feed and the iPhone Democratised publishing, accelerated Fragmentation (with a personalised pocket internet), supercharged Abundance (through an endless stream of information), and began the Corrosion of quality (as interruption beat authority).

Today, every public transport system around the world is filled with people doing nothing but scrolling. Millions of people right now are performing a simple gesture that didn’t exist 20 years ago: an upward flick of the thumb.

And if you aren’t relevant enough, you are scrolled past without a second thought.

Next time, the deepest and most important changes to our information environment:

Until then, thanks for reading. Please do subscribe, leave a comment, or share with other communicators that want to cut through the noise.

Take care and I’ll see you next week.

Simon